Jean

is in the third floor boardroom, stuffing ribbons of shredded paper

into extra large garbage bags. Piles of the stuff cover the long

table and spill on to the floor, softly mounded up on the chairs and

around the standing lamps like fresh snow. He half-smiles and tosses Zosia a roll of garbage bags, and they cram paper into the bags, pressing out the air

and cramming more, then tossing them into wheeled garbage bins. After

an hour or so they take the bins down in the freight elevators, dump

them and start over again.

"Did

you know this is the last day of work?" Jean asks. "That

the owner of the building has gone bankrupt?" He is the darkest

man she has seen. When she started the job she imagined everybody in a row, Jean at one end and Zosia at the other. La Polacka

gonna disappear in the snow, Filomena says. We're all like this back

home, Zosia tells her.

"Do

you know what they did, the geniuses in this building?" Jean

says. Zosia shakes her head.

"Imagine

that you buy a little house," he says. "You borrow money

from the bank, and then I go to the bank and say look, this

young lady is not such a fine credit risk for you after all. Let me

sell you insurance so if she can not pay, I will. I have no house, I

have nothing, only my suit and my briefcase and my talk. You

understand me OK?"

"Jean,

I don't know," Zosia says, smiling so he'll keep on. When he's

like this she can't follow half what he says but it's nice to hear

the even voice while she works.

"Do

you know what they did? Do you know what all of this paper is, the

people in this building and all these other office buildings, over and over and

over again? How can the credit insurance be more than the credit,

even more than the all stock markets in the entire world? These are the people that told us they knew how the whole world should

work, and that we should adjust our countries the way they

said. All of our economic and fiscal policy the way they said, in

Poland too, in Colombia and El Salvador too, and all the time they

were burning their own house down. My goodness," he says, "I

am an economist, I am supposed to know about these things, and I could not tell you what

fifty trillion dollars means."

"Do

you know what they said to us in my country, when people from my

office went to the World Bank? They said it is time for you children

to grow up, and to put away all of your toys. Put away your silly

price supports, and unions, and municipal water systems, and capital

market controls, and unemployment insurance, put away your silly

agricultural economists. Now your country has to stop being a baby and become a man, and it

is time to put away these childish things. You have to be realistic

like us, like our banks that are powerful and strong."

Zosia puts on an apologetic smirk because doesn't know what to say, but Jean isn't looking. He

walks around the walls, grabbing handfuls of paper and stuffing them

in a bag, bending and stuffing, his voice calm and steady. "I

met Mister Summers in Washington, do you know what he said to me? He

said, 'I know it will hurt for a while, little baby, to take your

medicine, but you need it to be big and strong like us.'"

He blows air slowly like someone breathing out cigarette smoke. "And you

know, I saw his face in the Wall Street Journal yesterday, and he is

saying that still."

They

toss the last of the garbage bags in the loading dock and start

wiping down the tables and the wall molding, then Zosia mops the

bathroom floor while Jean goes down to the big closet for the vacuum.

When the carpet is done it's nine-thirty, time to start packing up.

Filomena sticks her head in the doorway. "The union marching

here tomorrow on six," she said. "We all going, for our

jobs. For our jobs. OK, please you come."

It's

not a question but Jean sighs. "Sorry, I will not go. Me voy a

mi país,

OK?" He glances at Zosia. "It is time for me to go home

soon." Filomena

sighs, her shoulders sagging down a little. Her lips looked chapped and under her eyes it's dark. "I go, Filomena," Zosia says.

"OK

gorda, we will see you." Filomena turns back to Jean, and lays a

hand on his cheek. "Prenez soin de vous-même, mi negro."

"Et

tois, Fila," Jean says. When she goes they stuff the last of the

bags into the rolling bin.

At

the swipe clock, Sue Ellen clutches Zosia's hand with damp fingers.

"Go on down to the personnel office honey, they need to put you

on the list. I'll tell them you're a good little worker, not like the

rest of these. Here in America that will always see you through."

"Goodbye,

tępa

cipa." Sue

Ellen's hug stinks. "Oh honey, I don't know what that means but

I'm sure it's something sweet like you."

"OK,"

Zosia says.

Back

in her room in Eastie, she doesn't try tonight to think about the

forest, about the movies she likes where cars race the wrong way on

freeways jumping bridges with boys shooting the heads off boys on the

fly, about the fairy tale where Zosia is some kind of angel on a cool

journey, a clever pirate: she just shuts off the light and cries. A

cold draft blows across her feet. On the seventh floor of a crappy

council flat in Warsaw, water is dripping on to the metal siding. Her

mother's teeth are floating in a cleaned-out jam jar, her sisters are

laying their school uniforms over the tops of chairs, and Zosia's cat

is looking for the warmest place he can find, sneaking across the bed

covers to nestle on somebody's head until they shove him away.

After

crying she can sleep. It's a cloudy night and the planes are roaring

low over the house, to the runway a quarter mile away. Zosia wraps up

and feels herself a small, pretty shell, polished to a dull shine: a

button on a coat.

3

It

never seems like two years: sometimes half a year, sometimes almost

her whole life. The plan was a a year, maybe. At the last minute,

before getting on the plane she even thought in a panic about the

army, but the idea of Afghanistan, where her classmate ended

up-ended- or someplace worse, and they hardly even pay anyway. Mama

says it'll be better, with the European Union, everything costs more

but you can work in London, Munich, anywhere. And come home to visit

all the time.

Zosia's

neighborhood in Warsaw was not like the ladies talked about at work,

like Ana told her one night about some of the Colombians' towns: the

army then the narcos, shooting everybody, raping everybody. Burning

the gardens and the houses. The Dominicans and the Haitians too, Ana

said, and in the DR the money all of a sudden was worth like half, so

you could stay and give tourists blowjobs or you could get some money

from your cousin and get on a plane.

Her

building, at least, wasn't like that. The neighbors were nice but

Zosia and her sisters heard guns, and cops: blood puddled on the

ground. Mostly it just kind of fell apart: people moved out of flats

and nobody came in, the cement broke and crumbled, glass dropped out

of the window and hit the deaf child. And the water pipes all started

leaking, and after a while nobody came to fix any of it any more.

That's how it went.

She's

finally figured out the buses and trains. After her day job she

watches the warm rain patter on the window, sipping a paper cup of

sweet coffee that steams up her nose. Someone has left a newspaper on

the seat and she slowly reads the headlines, thinking of what Jean

said the day when he was doing floors in her area, spreading wax with

a wet mop. The way he went on sometimes reminds her of the boy, who

talked about being a tycoon, coming over to American where you can

start a business without the whole goddamn world on your case.

I'll

come right away, he said, I don't care about my mother and them's

crap, every single year she's on her last days, she has only a little

while left on the earth. In an old-lady voice, All I have left are my

memories. His pale rib cage and concave belly floating up and down,

talking talking talking until she finally said, you got another

condom?

The

headlines are all about banks unwinding, and Zosia imagines a giant

sweater over the city, the threads loosening and the arms and back

melting away. At the laundry the old white women and Vietnamese men

say good morning, and she works by the radio, and at noon the lunch

truck comes. All day she sent text messages to Ana: R U still going?

In the day, on the bus or the subway, Zosia likes it here, where she

doesn't hear all the time from Mama and the other unemployed ladies

all day long, her sisters needing braces, the crappy toilets, the

politicians, everybody's aches and pains.

At

night it's different, she knows.

She

feels the drums from the march in her stomach when she walks up out

of the subway, shouting and air horns getting louder as she walks the

two blocks toward the corner where they're meeting. Already a big

crowd in front of their building, spilling in to the street where the

cops' motorcycle lights twinkle in the dusk, setting up a barricade,

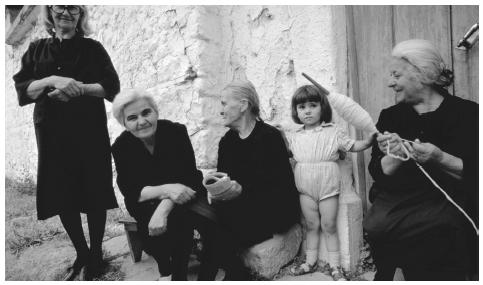

and there's Filomena and Ana with their little flags and hats.

Filomena is talking to two other women from their crew, making a

story with her hands in the air. Filomena and Ana put their arms

through hers and they walk up the street toward the crowd. Zosia was

always in the middle, her sisters on either side, trying to stray off

at the bakery or chase after their little friends so she clutched

their arms and pulled them in and mama said that's a big girl,

looking after everyone. She wrenches her arm away and

drags it across her eyes.

"Don't

worry, girl," Ana says, and then Gustavo's leaning against the

building, blinking his red eyes at her.

"No

te preocupes llorona." He grins. "Your man here to you."

"Cállate,

dupek," Filomena says. "No talking now, marching."